Henry F. Skerritt

AN ODE TO WOMPI

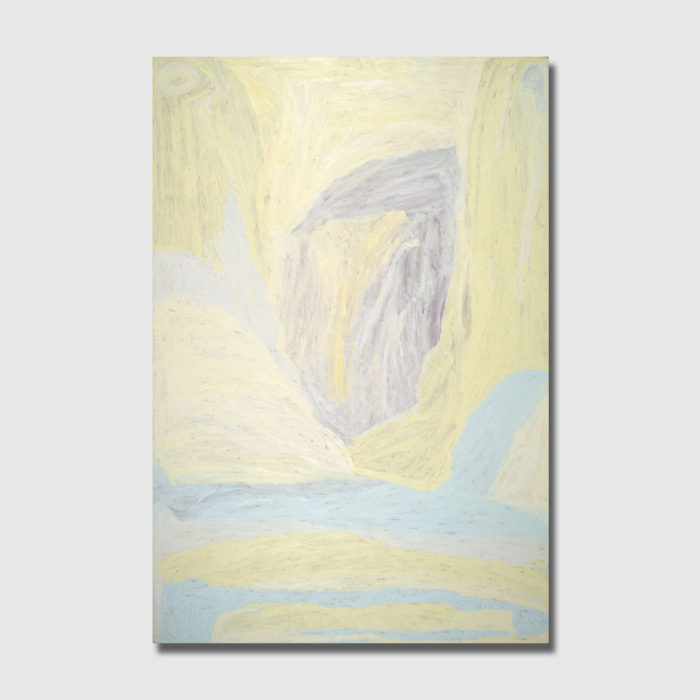

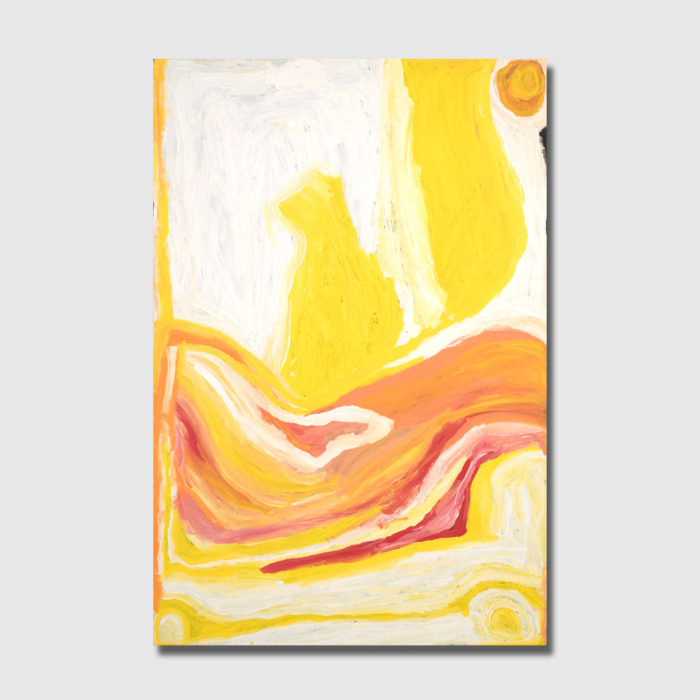

Let us stand before a final masterpiece. With reverence, let ourselves to be swallowed by its breathless economy of marks; its whispered silences like that final notes of a profound requiem. Let us take a moment to be quiet in the lingering presence of genius. Big Tuwwa at Philip Bell’s birthplace at Ngara Apal Bolgo Kakarra (2015) was painted in the last years of Wompi’s life. Like all her best works, it is painted with the unmistakable confidence that marks her as of Australia’s finest gestural painters. But it is also a work of extraordinary calm. It is the work of an artist on the cusp of their return to the ancestral realm. This is a different confidence to the typical bravado of abstract expresssionists: it is a painting whose self-assurance is drawn from the artist’s unity with their world, their becoming one with the land from which they came.

As we pay our respects to this under-heralded titan of Australian painting, it is worth considering how Big Tuwwa at Philip Bell’s birthplace represents both the culmination and continuation of Wompi’s remarkable artistic project. This exhibition offers a remarkable opportunity to survey the works produced in the final seven years of Wompi’s life, as she moved between working with Warlayirti Artist at Wirrimanu (Balgo) and Martumili Artists in Newman. This covers a period of increasing minimalism in Wompi’s practice, as the defined line work, circles and dots of early paintings were increasingly replaced with broad fields of gestural colour. This shift is clearly evident when one compares works from 2010, such as Yurunkurnpa 2010 [10-1185] or Kunawarritji Community (Well 33) 2010 [184/10] with the breathtaking grace of works such as Kunawarritji 2012 [248/12] or Untitled 2015 [15-973].

How might we interpret this move? With their thick, viscous skeins of impasto paint, Wompi’s paintings seem to melt onto the eye. Layers of overlapping colours blur, making forms difficult to define; the desert landscape shimmers into being, like a mirage upon the horizon. The movement of the artist’s hand is clearly visible in the thick brushstrokes, which run across the canvas like trails in the wilderness. The encrusted dots of early works have gave way to broad swathes of shifting colour. Where the early works had a gravelly sense of place that evoked the material presence of the landscape, Wompi’s late works present a much more peripatetic, nomadic understanding of space.

After 2005, Wompi’s paintings increased in both scale and confidence. But her development should not be seen as a process of metamorphosis, so much as an artistic form of artistic excavation, stripping away the crust to reveal the metaphysical essence of the landscape. In this sense, her final works might be read as being less concerned with the visible features of the landscape than with its underlying spiritual meanings. They are paintings of experience, not cynical or world-weary, but acutely aware of the truth of the matter, of what is permanent and what fades away. Exploring this intangible essence required Wompi to develop a unique abstract, and highly phenomenological, visual language. The clearly identifiable iconography of desert painting – with its recognisable symbols for waterholes, campsites and rockholes – was slowly replaced with a more fluid, gestural style. The specificity of particular places, stories and sites gave way to grand, totalised renderings of her country around Kunawarritji. These are ‘big pictures’ that required a ‘big picture’ approach. The spiritual essence that they seek to capture cannot be described

using a predetermined lexicon of signs, but required the development of an artistic language based on emotion and intuition.

Born around 1934 at Lilbaru near Well 33 on the Canning Stock Route, Wompi belongs to a fading generation of senior Indigenous people who grew up in the desert, learning the solemn codes of the nomadic lifestyle. Consistent with this nomadic outlook, her biography is defined by significant travels: walking with her mother to Bililuna Station and then onto Balgo Mission; relocating to Fitzroy Crossing with her third husband Cowboy Dick; returning to Kunawarritji with her sisters at the dawn of the homelands movement. Although aged in her late seventies, Wompi maintained a highly transitory lifestyle, moving regularly between Kunawarritji, Balgo, Kiwirrkurra and Punmu in order to visit relatives and attend to familial obligations. Wompi’s early works were largely produced through the Warlayirti Art Centre at Wirrimanu (Balgo). After 2010, Wompi increasingly worked through the newly formed Martumili Art Centre based in Newman. It was around this time that Wompi’s work became increasingly abstract, as she worked alongside other senior artists Nora Nungabar and Bugai Whyoulter.

For Western Desert peoples, places are not understood in isolation, but rather through their intersections and connections. This reveals itself through the songlines that run across the country, uniting all places. These paths reflect the ancestral cosmology of the Dreaming, when spirit beings traveled across the landscape creating its sacred sites and leaving their residue in the landscape. For Indigenous people, this sacred essence remains in the landscape, and is discernible to those whose kinship or custodial ties allow them to access it.

It is this pervasive presence that Wompi explored in her paintings. In their sinuous pathways, we see an organic lattice of places, each connected, rolling into each other like tali or sandhills. Each gestural mark upon the canvas is like a footprint, revealing its creator’s presence. Like a footprint, they exist as the memory of presence – a nostalgic echo of past travels, both personal and ancestral. Judith Ryan has characterized this as a “haptic quality … calling sites and spiritual associations through touch.” This touch connected Wompi’s knowledge and custodianship of the land to that of her ancestors; her movement on the canvas becomes a mythopoetic recollection of all the spiritual travels that underpin her country. At the same time, it overlays her own journey – both physical and artistic – creating a palimpsest that connects the past and present.

In doing so, Wompi’s paintings create a matrix that unites all time and place. They paint the history of her landscape, as it is transcribed by ancient songlines and transgressed by more recent paths, such as the Canning Stock Route, which, during Wompi’s lifetime, brought European settlers into the world of the Kukatja. These settlers could not see the landscape, access its sacred powers or read its songlines. But perhaps this is the very point of Wompi’s paintings. As their lines of colour spill outwards to the edge of the painting, it is almost as though they are trying to break free of the canvas, to pour out from Kunawarritji to the world. As they reach the edge, they ask us to see the majesty outside the canvas – to realise that this mystical essence is part of the great continuum of existence. And so we stand before a final masterpiece. Conditioned as we are to hail individual genius, we might want to shout the artist’s name: herald them with trumpets and fanfare. But the artist is gone. What is left is the earth: something greater and more enduring that human accolades. On canvas we are left a whispered trace of a genius loci that was and always will be, past-present-future, as Wompi becomes one with the ages.

Henry F. Skerritt

Curator of the Indigenous Arts of Australia at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia.